FDA Orange Book

The Orange Book, formally known as "Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations", is a publication that provides consolidated intellectual property, exclusivity information, and therapeutic equivalents for FDA approved brand name drugs.

Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, more commonly known as the Orange Book is a publication containing FDA approved drugs, associated patent and exclusivity information, and therapeutic equivalents1. Today, the Orange Book is an important reference for medical professionals, industry business development, and the public. Here we will briefly cover the history and contents of this important publication.

Where did the Orange Book Come From? #

The original Orange Book was created via federal rule making in 19802. In the initial proposal, the FDA cited the following as primary motivations for establishing the publication:

- Education

- Cooperation with state medical authorities

- Combating inflation

Education and State Cooperation

Before the 1970s, when a physician prescribed a brand name drug, most state laws required the pharmacist to dispense exactly that brand of drug, even if a cheaper and equivalent generic option existed. This was a popular state of affairs if you ran a drug company. Indeed, the initial Orange Book proposal described efforts by drug companies and medical societies to confuse the public about therapeutic equivalents, with claims that “special coatings” or “fillers” caused proprietary drugs to be more effective than generics. One comment from a campaign even stated that “chemically equivalent drugs may not have the same effect”, and gave the example of diamonds and coal both being pure carbon3.

Despite these campaigns, from 1970 to 1977, physicians were prescribing drugs based on generic name (the non-brand name of active ingredients) at an increasingly frequent rate, and partly in response to high drug costs, education, and inflation, state laws were changing to allow pharmacists to dispense the lower cost equivalent option4 when available.

By 1979, 40 states and the District of Columbia had enacted so called “drug price substitution laws” – a dramatic turn from virtually all states having “anti-substitution laws” before56. With these new laws and prescribing trends amongst physicians, pharmacists had a greater responsibility to identify (and keep stocked) the appropriate drugs to dispense to patients. But with no authoritative list of approved brand name drugs and therapeutic equivalents, this was a challenging task.

State medical authorities wanted an authoritative list to help providers accurately substitute drugs, and some states, including New York, created their own7. FDA notes that by 1979, 19 states and the District of Columbia had approached FDA to help create state lists – further emphasizing the need for a central, authoritative list.

Inflation

By 1974, inflation had reached nearly 12%, in 1980, it would peak at 13.5%8. At a press conference in 1978, President Carter noted:

One of the very discouraging aspects of our present health care system is the enormous increase in costs that have burdened down the American people. The average increases in cost of health care per year has been more than twice as much as the overall inflation rate.

Encouraging the use of therapeutically equivalent generics represented an opportunity to dramatically cut healthcare costs without sacrificing the quality of care for Americans. And a simple step towards this goal would be letting people know cheaper alternatives exist.

The First Publication

In response to requests from state health officials and medical professionals, the FDA established “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations” via federal rulemaking and the first issue was published on October 31, 1980, hence the name529.

The publication was codified with the passage of the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 19841011, and the patent information and exclusivity information was also added.

What Type of Information is in the Book? #

The Orange Book and associated electronic resources are currently maintained by CDER.

While the initial Orange Book contained only approved drugs and equivalents, the current Orange Book contains11:

- Approved drug products and therapeutic equivalents

- Patent and exclusivity information for approved drug products

- Approved over the counter drug prodcuts

- Drugs products approved by CDER (under section 505) but administered by CBER

- Cumulative list of approved products

Importantly, the Orange Book contains only approved drug products regulated by CDER, so tentative approvals and some biologics regulated by CBER are not included12.

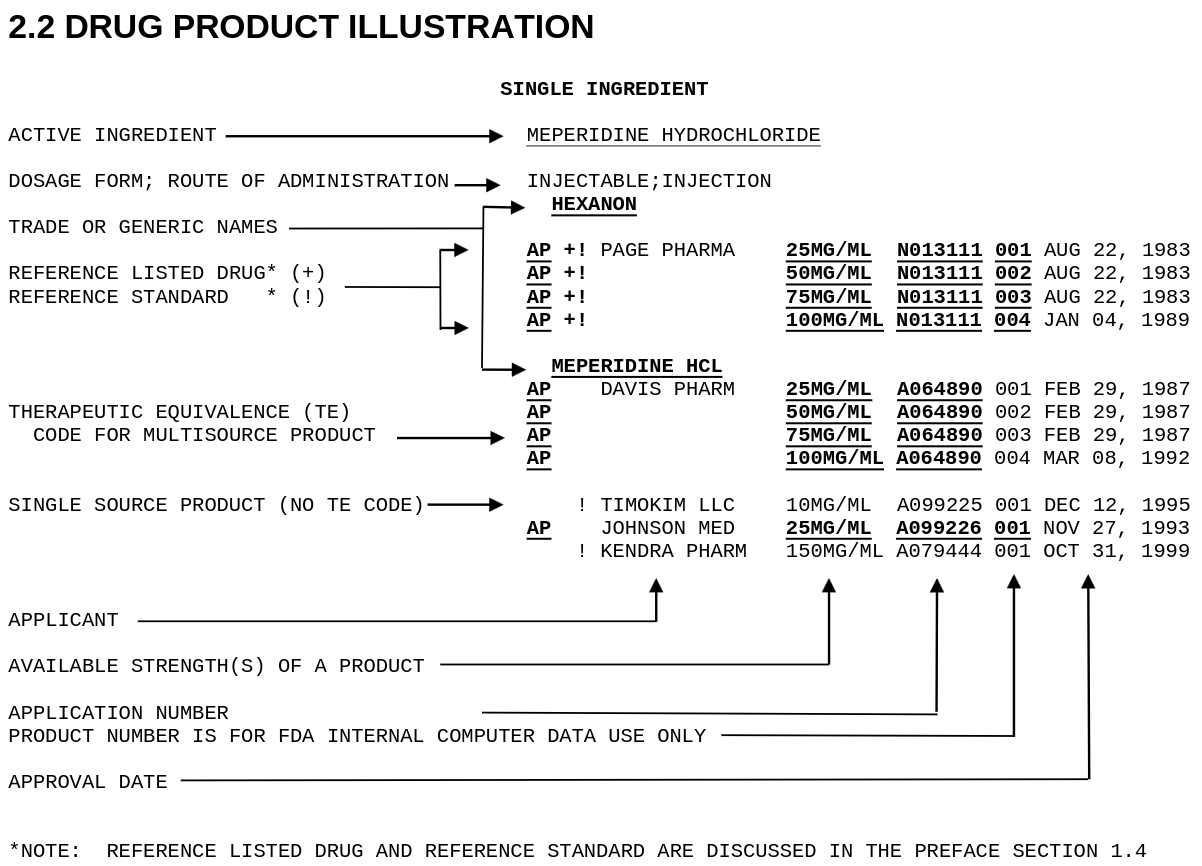

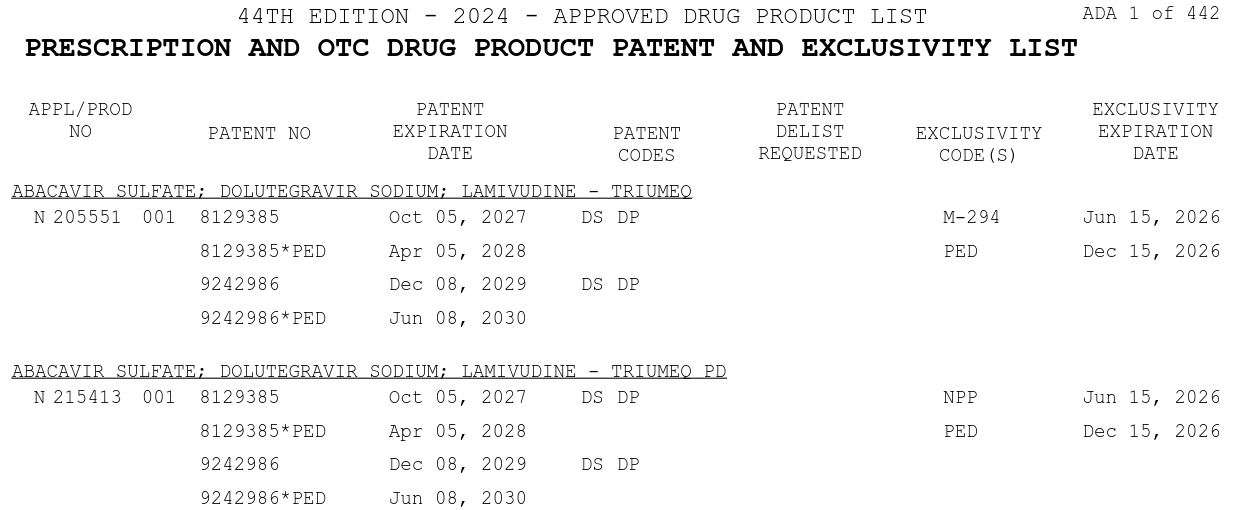

The annual Orange Book Publication is available from FDA. The text version is dense, and difficult to analyze, for example, here is figure 2.2 from the 44th edition (2024).

Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) codes are the key to determining whether a product can be substituted for a brand name drug. Codes beginning with “A” indicate equivalance, and codes beginning with “B” indicate the generic is not considered equivalent.

Patent and Exclusivity Information

The Orange Book also contains patent and exclusivity information about prescription and over the counter drug products.

The patent information is provided by applicants and is not necessarily validated by USPTO or FDA. Note that the latest patent expiration is not necessarily the same as the exclusivity date due to additional FD&C exclusivity. Patents within the Orange Book can be challenged for accuracy and often are13.

How can you use the Orange Book? #

The Orange Book was initially intended as a resource to provide medical professionals with a list of approved drugs and their corresponding therapeutic equivalents. However, we are more often using the Orange Book to better understand the exclusivity and intellectual property restrictions surrounding a particular drug or active ingredient. Since patent entries in the Orange Book are not verified by the FDA, applicant holders can, wittingly or not, add false information or non-applicable patents to the Orange Book. This can drastically extent the exclusivity period for a drug, delaying generic entry and keeping prices artificially high. The FTC has recently taken an interest in reminding companies13 that they have a responsibility to follow the law and ensure entries are accurate.

Today, the Orange Book is available as an annual publication and a monthly electronic format. We’ve created a drug exclusivity dashboard that tracks the FDA Orange Book and USPTO data to predict when drugs will expire. This dashboard is updated monthly when new editions of the EOB are released. If you need help analyzing data or assessing exclusivity terms, we are here to help!

See 45 FR 72582 for initial rule establishing the orange book. ↩︎ ↩︎

The campaigns, including motion pictures narrated by popular actors are described in 44 FR 2932 p184. ↩︎

The FDA defines a therapeutic equivalents as one that contains the same active ingredients and method of action, and has undergone approval through an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA). ↩︎

For a more detailed history and the request for comments on the proposed rule, initially published on January 12, 1979, see 44 FR 2932 ↩︎ ↩︎

The 1979 FTC Staff report (PDF) titled “Drug Product Selection” contains a detailed history of antisubstitution laws, the transition to substitution laws, pricing, and estimated savings from adopting substitution laws. https://www.ftc.gov/reports/staff-report-drug-product-selection ↩︎

see New York Drug List, April 1, 1978 p185 44 FR 2932 ↩︎

The orange color for Halloween publication was described by Captain Kendra Stewart in a perspective piece looking back at 40 years of Orange Book publications ↩︎

Commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Amendments to the FD&C act, this law formalized drug exclusivity, generic approval via ANDA’s (505j approval) and much more. ↩︎

See more in the Orange Book preface. ↩︎ ↩︎

Tentative approvals can be found in the Drugs@FDA database, and biologics are listed in a less-comprehensive purple book ↩︎

See the FTC Patent Listing Challenges from April 2024 and Statement on Improper Patent Listings ↩︎ ↩︎